Editing Buildings

The Running Reality desktop app provides tools to edit buildings, including their structure, condition, location, and events that happen to them. It also handles data uncertainty with multiple techniques.

Overview

This tutorial covers buildings, how they are represented in historical maps and other data, how they are represented in Running Reality, how to edit them, and how to handle uncertainty. As buildings are such a central element of cities, we have worked hard to represent them well and have plans to improve how we represent them into a 3D future.

Download AppGIS For users familiar with GIS systems, you are probably used to data with modern precision and buildings represented as a polygon with metadata. This article talks about how we have to handle temporal and geographic uncertainty. To do this, there are some conceptual differences from GIS systems. Also, Running Reality represents objects with a timeline as their primary data structure, not their geometry. Geometry is one kind of data on the timeline, but other data like events might be on the timeline.

Editing Building Data

The basic editing tools for buildings are located in the building's sidebar. There are many

geographic and non-geographic types of data that can be added to a buildings timeline. Use

event and exists factoids to set the building's timeline. Add events

to tell the history of the building, especially including things like fires. Multiple kinds of

structure data can be added, including a 2D polygon footprint, a 3D structure, and a more generic

condition.

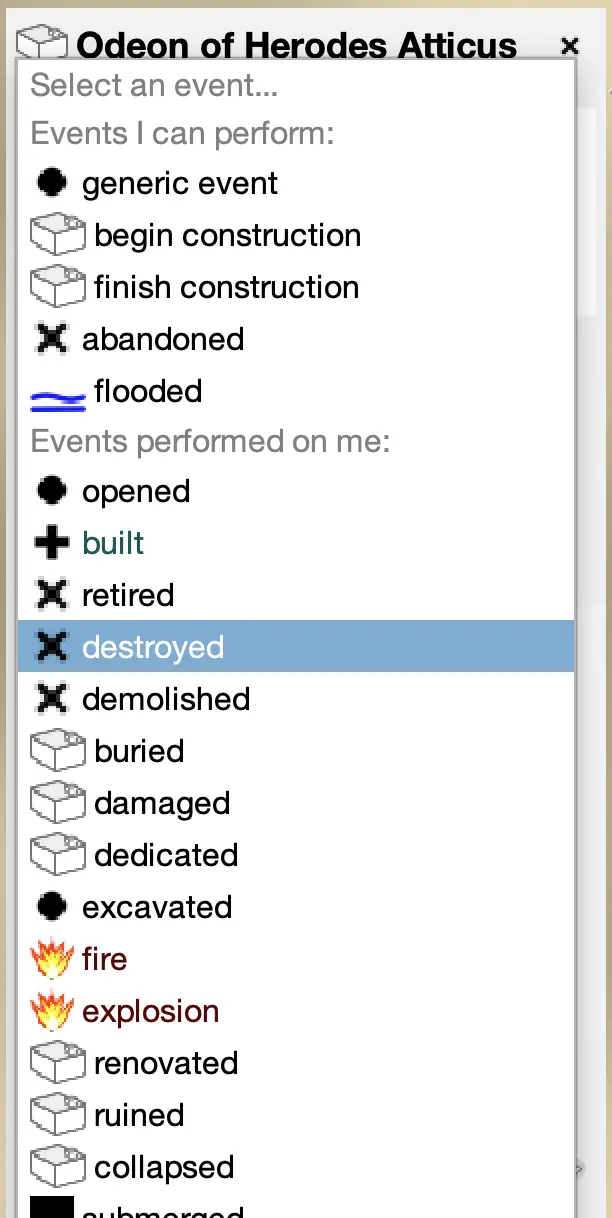

Adding event data to a building. Click the

Adding event data to a building. Click the ADD EVENT button in the building's sidebar.

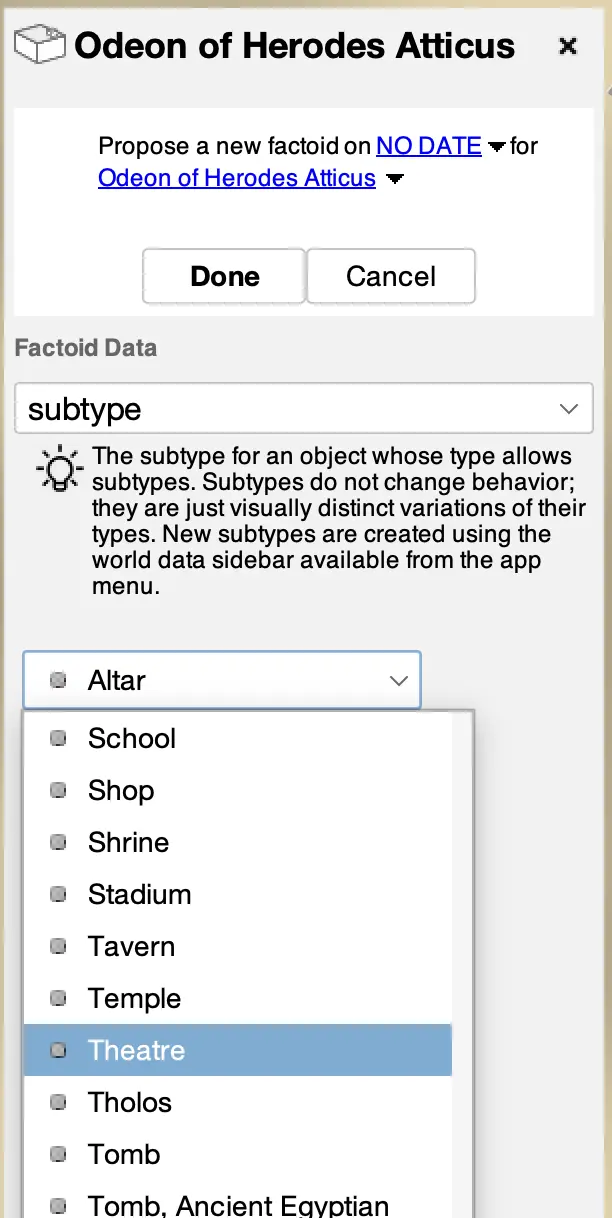

Adding a subtype to a building. Click the

Adding a subtype to a building. Click the ADD OTHER button in the building's sidebar.

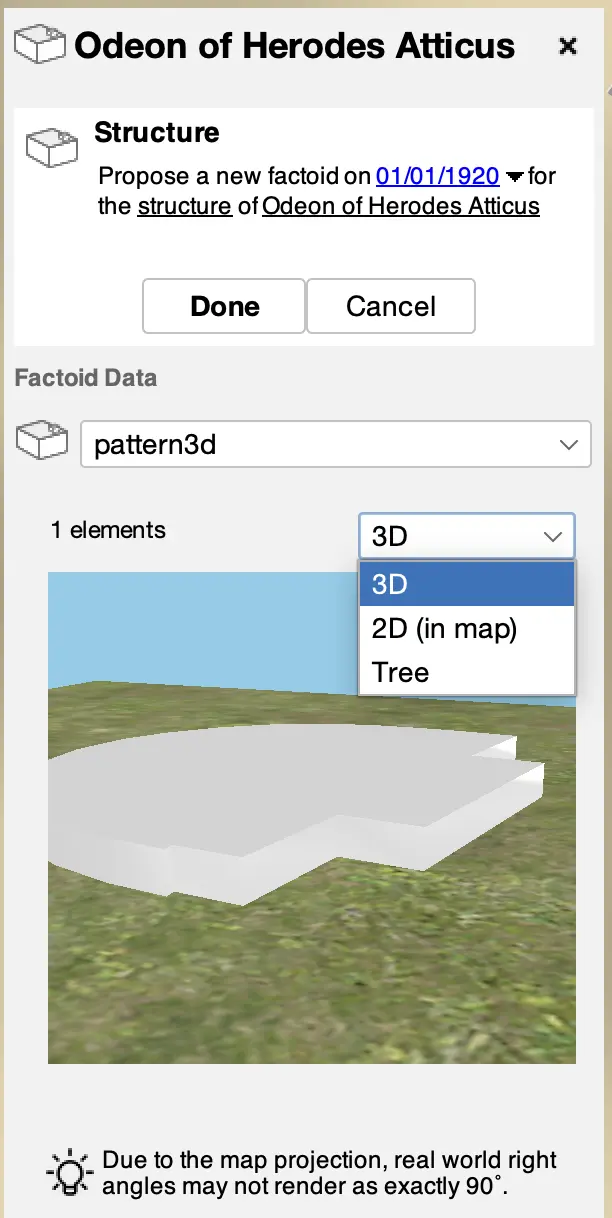

Adding 2D or 3D structure to a building. Click the

Adding 2D or 3D structure to a building. Click the ADD DATA button in the building's Structure panel in its sidebar.

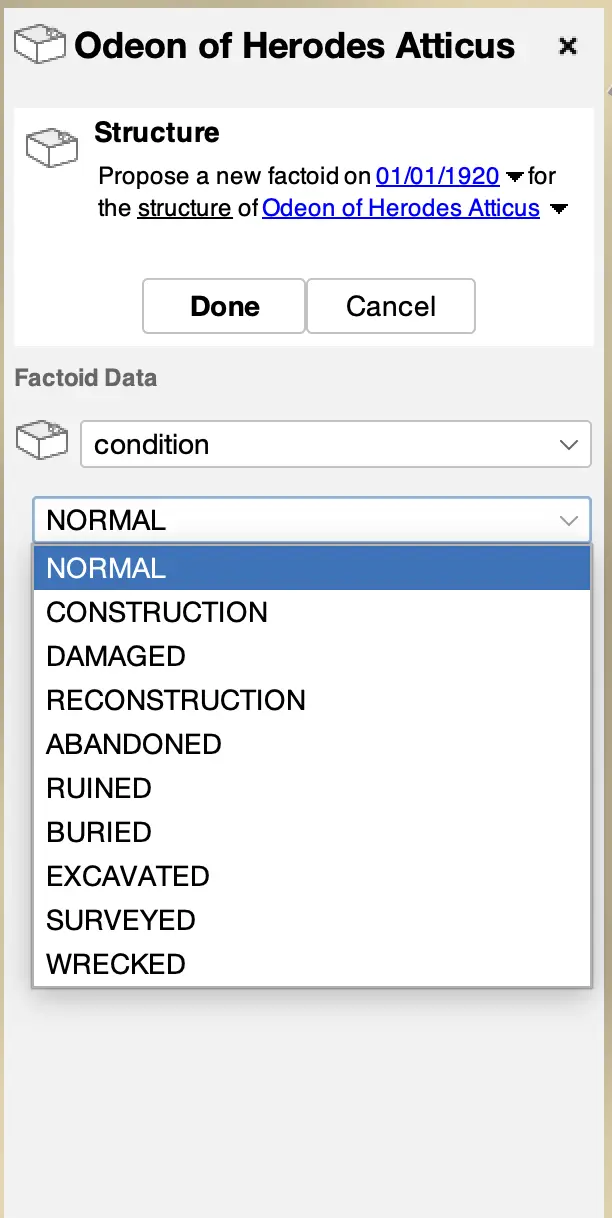

Adding structure condition data to a building. Click the

Adding structure condition data to a building. Click the ADD DATA button in the building's Structure panel in its sidebar.

NOTE Types and subtypes are not temporal data. We strongly encourage using other temporal factoid data. However, buildings are sometimes most easily categorized by their subtype and this subtype information can be very useful to the history engine when making inferences. Buildings that have only had one use through their history are good candidates for a subtype, such as a temple, theater, or house.

Editing Locations

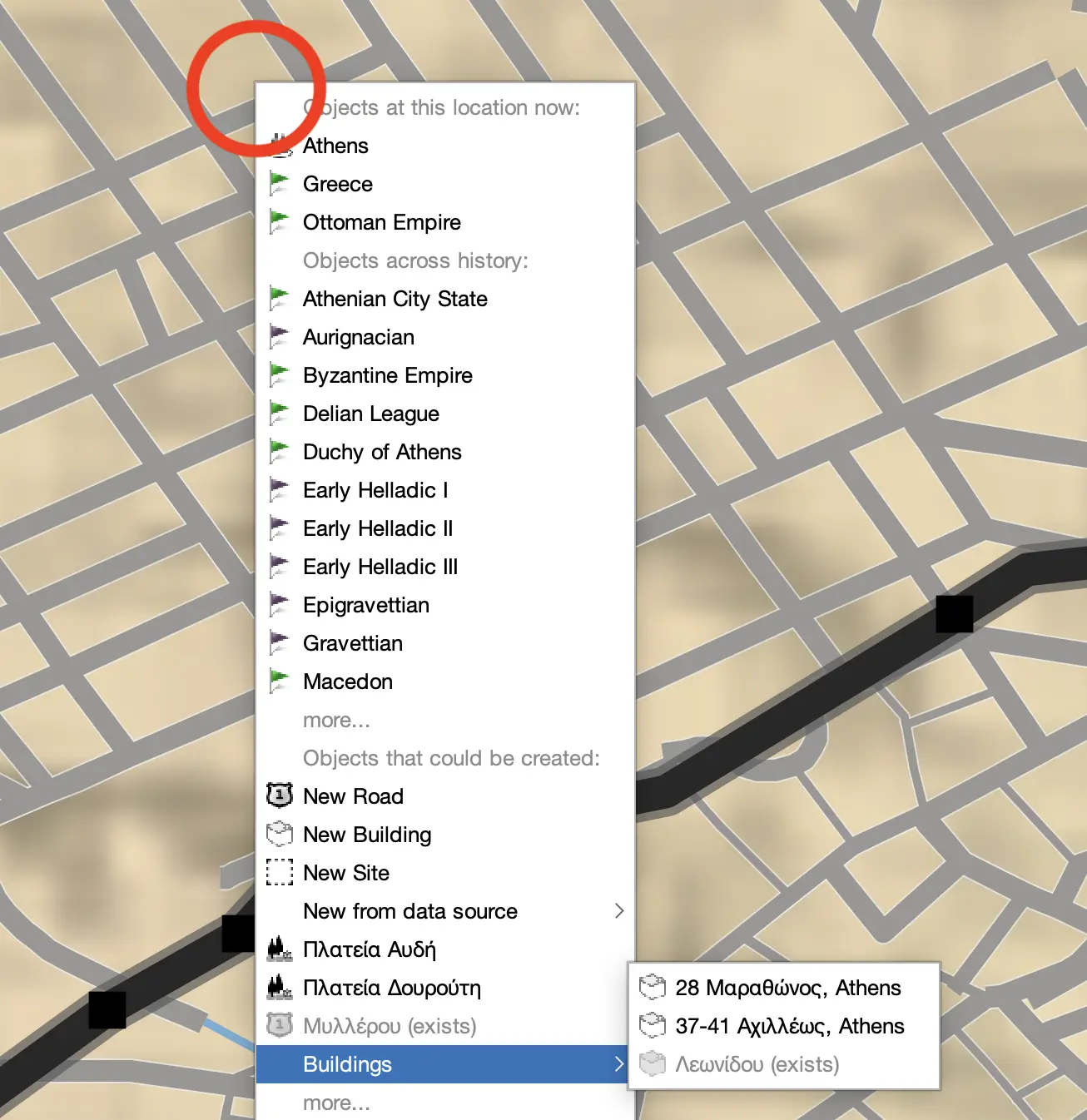

Adding a building usually starts from a location. Sometimes you have only the location and no name, structure, or date data. If you right click on the map, you can directly add a building at the spot using the pop-up menu. This will let you create a generic building at that location or you can import a candidate from a data source like OpenStreetMap.

Editing a building location. Click to place the location and click again to move it.

Editing a building location. Click to place the location and click again to move it.

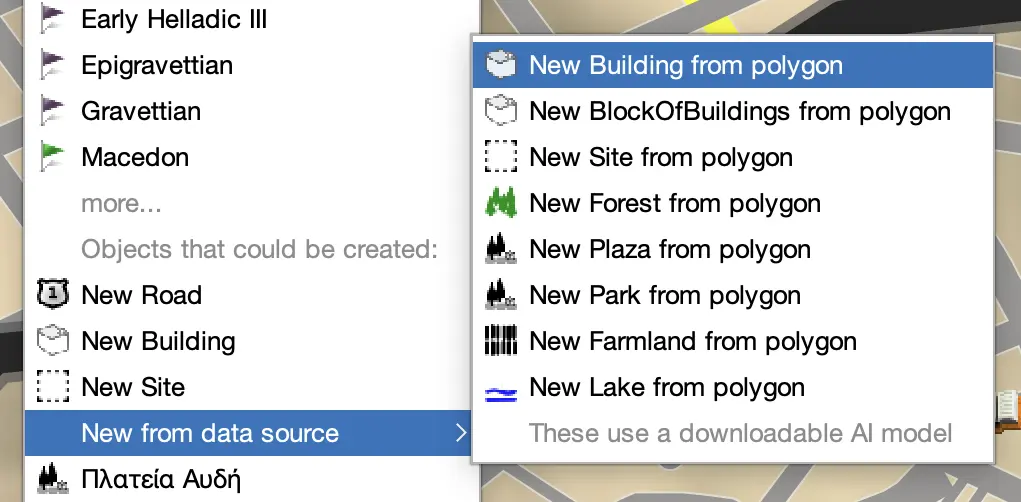

Using a right mouse click, import a candidate from a data source. This will use an AI

Machine Learning algorithm to identify a polygon in an layer at this location.

Using a right mouse click, import a candidate from a data source. This will use an AI

Machine Learning algorithm to identify a polygon in an layer at this location.

Using a right mouse click, import a candidate from OpenStreetMap for this location.

Using a right mouse click, import a candidate from OpenStreetMap for this location.

GIS For users familiar with GIS systems, the polygon footprint data is also the location data. Running Reality separates these because the location doesn't change over time, but the structure (and therefore polygon) does change over time. The position may have a separate citation and the structure may have multiple citations over time. Often, there is only location data but no structure data, and the absence of structure data signals the history engine to use its inference engine.

NOTEImports from OpenStreetMap usually come with both a location and a footprint already. The location and structure will have factoid dates of the current day, regardless of the date of your map during editing. These imports use the OSM Overpass server, which can sometimes be overloaded and give you a network error.

Editing Footprints

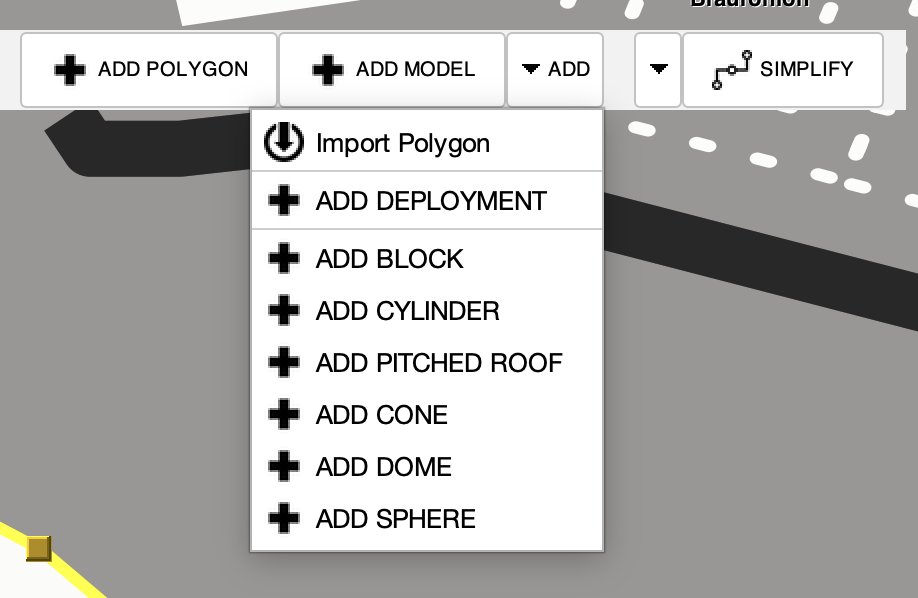

The basic structure data for a building is a 2D footprint. These can be comprised of multiple elements such as blocks, cylinders, polygons, etc. For the simplest buildings, consider using a simple block. If you have more detail on the footprint, then use a polygon to capture the details. Add new elements from the toolbar menu. You may also import a polygon from a data source, including OpenStreetMap, using the same AI Machine Learning model mentioned above.

The editors for the elements are similar to those of other in-map editors in Running Reality for adding and deleting vertices. If there are multiple elements, click to select an element to make that element's editing controls visible.

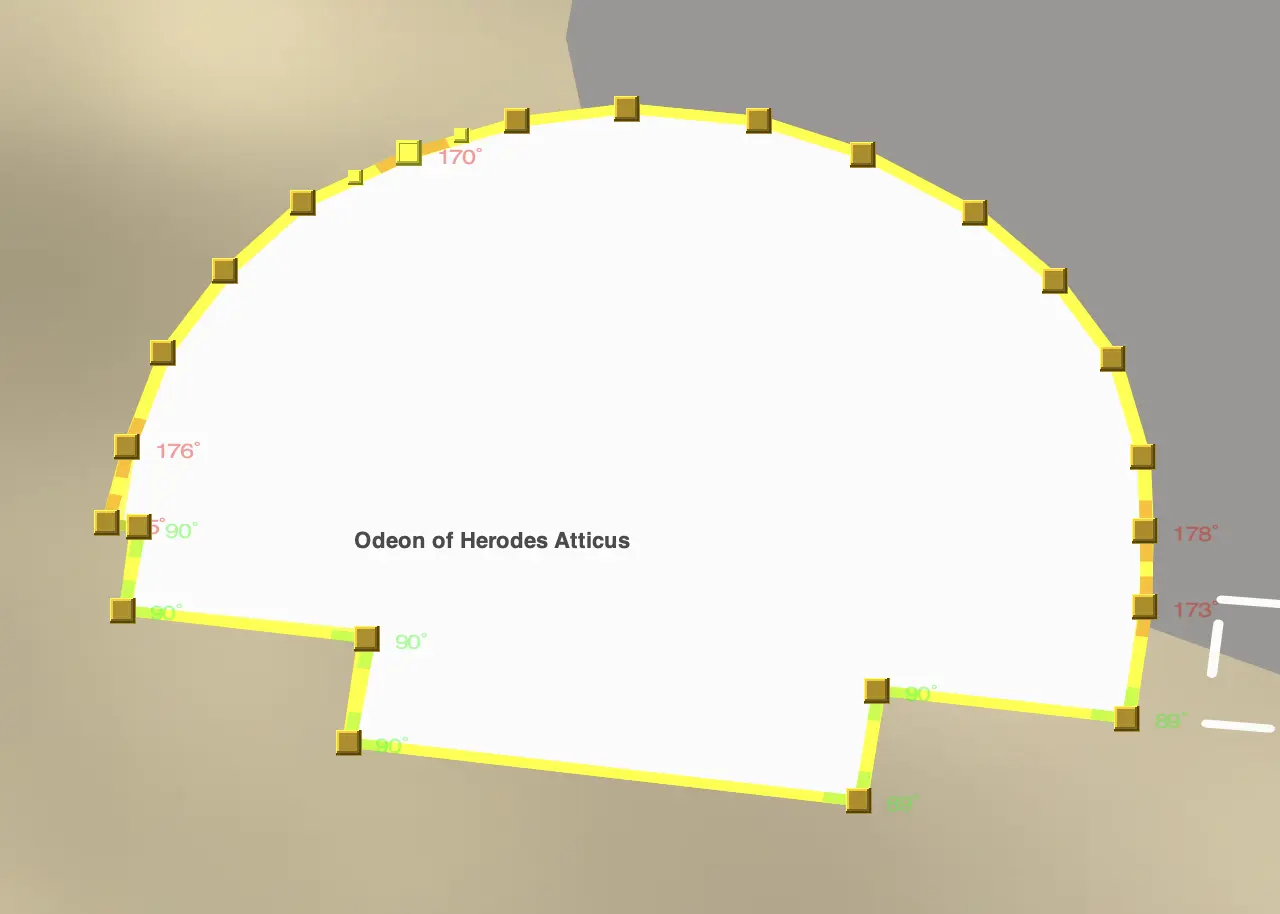

Editing a polygon footprint. Note the corners are color coded from red to green as they

approach 90 degrees.

Editing a polygon footprint. Note the corners are color coded from red to green as they

approach 90 degrees.

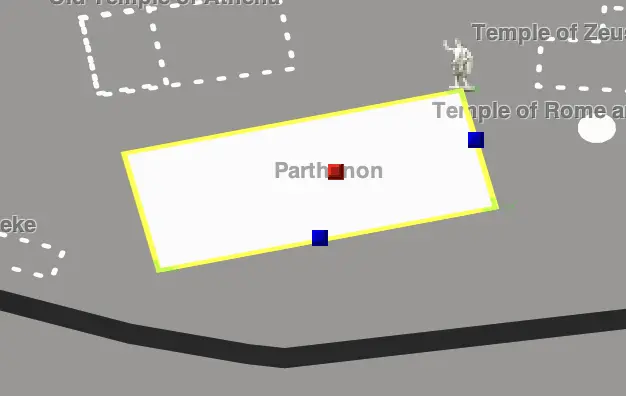

Editing a simple block footprint with blue sizing controls and a red rotation control.

Editing a simple block footprint with blue sizing controls and a red rotation control.

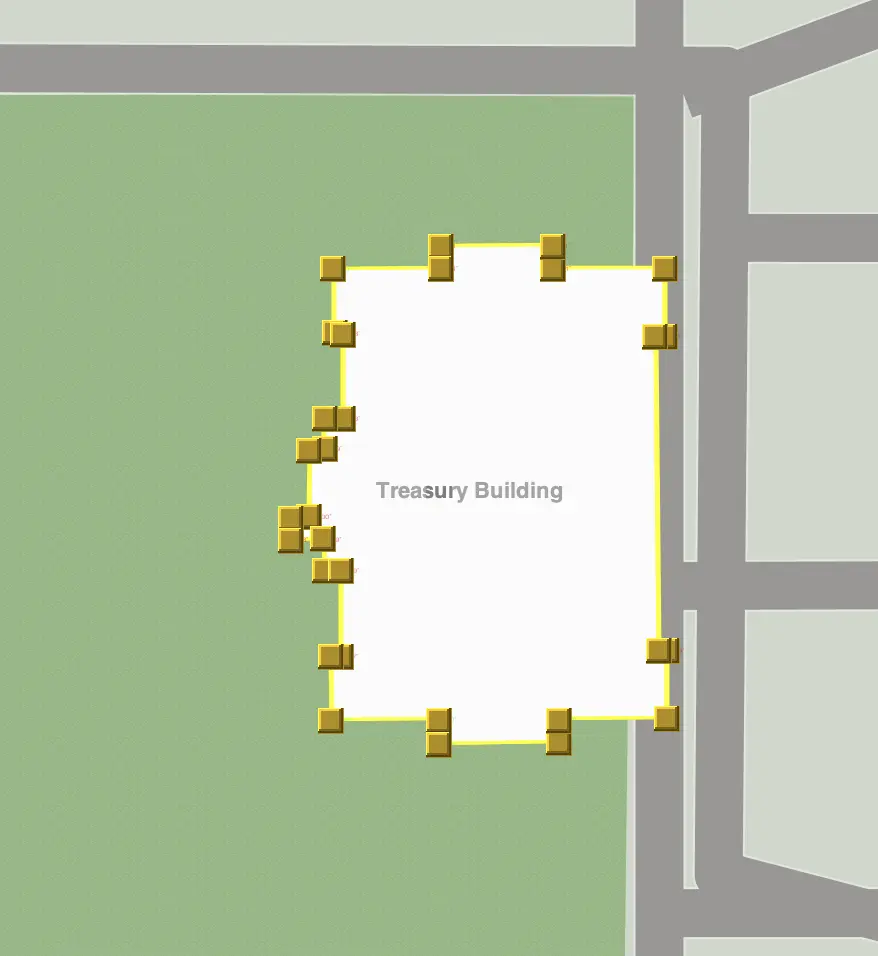

Editing a polygon footprint that was imported from OpenStreetMap.

Editing a polygon footprint that was imported from OpenStreetMap.

For more advanced editing that is halfway between 2D and 3D editing, you can also set a material on each element and a height. In the materials menu, there are a set of basic materials that either set a color or a physical material. This can also be used to add gardens or water that are part of the building itself. The set menu has presets for setting the height of an element in meters, number of stories, or flat on the ground. See below for more about 3D editing.

NOTE Angles may not appear on screen to be exactly 90 degrees even when they are. This is due to the app's map projection being Equirectangular and not Mercator. Mercator maps preserve right angles through rotation, but other projections do not. Use the color coded guides to get the angles square. The app will move to a Mercator projection as part of its transition to a 3D map.

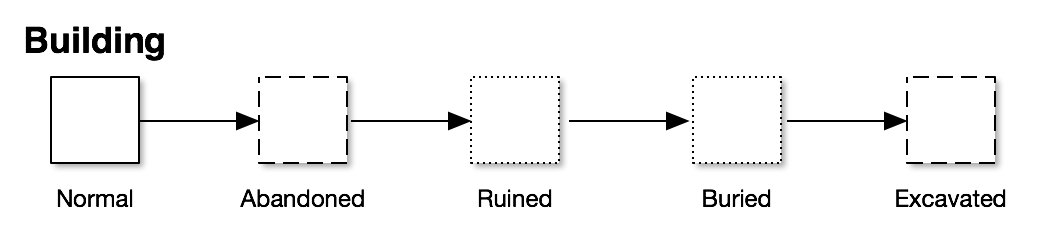

Uncertainty: Conditions

Running Reality tracks the structure's condition over time as well. Often, the condition is known but not the detailed structure. For instance, literary sources may indicate that a building was abandoned, but we do not have enough information to implement a new 2D footprint or a 3D model. Addition condition factoids give more historical context about a building and can help the history engine perform better inferences.

If you know the date when a building was abandoned or ruined, such as the date of an earthquake, then use

an abandoned event. Otherwise, if you only know that the building was abandoned in 1400 but not the exact

date, then add a structure factoid for condition = abandoned on 1400. Event factoids versus data factoids

will result in the engine using different interpolation / extrapolation rules for the timeline of this condition.

If we know a building was abandoned sometime in the 14th century, a basic approach is to try to model

this as an abandoned event in 1350 with an uncertainty of 50 years. However, that "knowledge" is very often

a human inference, not data. What we usually really know is that the building was in use around 1300 (e.g.

maybe due to a coin or pottery) and abandoned by 1400 (e.g. dating of soil on the floor or a written text

by a traveler). If possible, it is usually better to record the direct evidence of a building's condition

on known dates and then let the Running Reality engine do the interpolation. That way the inference is

explicitly done by the engine and not baked into the data set. Far too often, baking in such an inference

leads to having to delete that factoid later because someone just found a reference to the building being

in use in 1310.

If you see what the engine is inferring is wrong, that means you have additional data. That data can then

be entered so that the engine can improve its rendering. For instance, you can give a new building footprint

to show just how little might be found to remain after excavation. Or you can add an additional exists

factoid if a building should persist further back into the past.

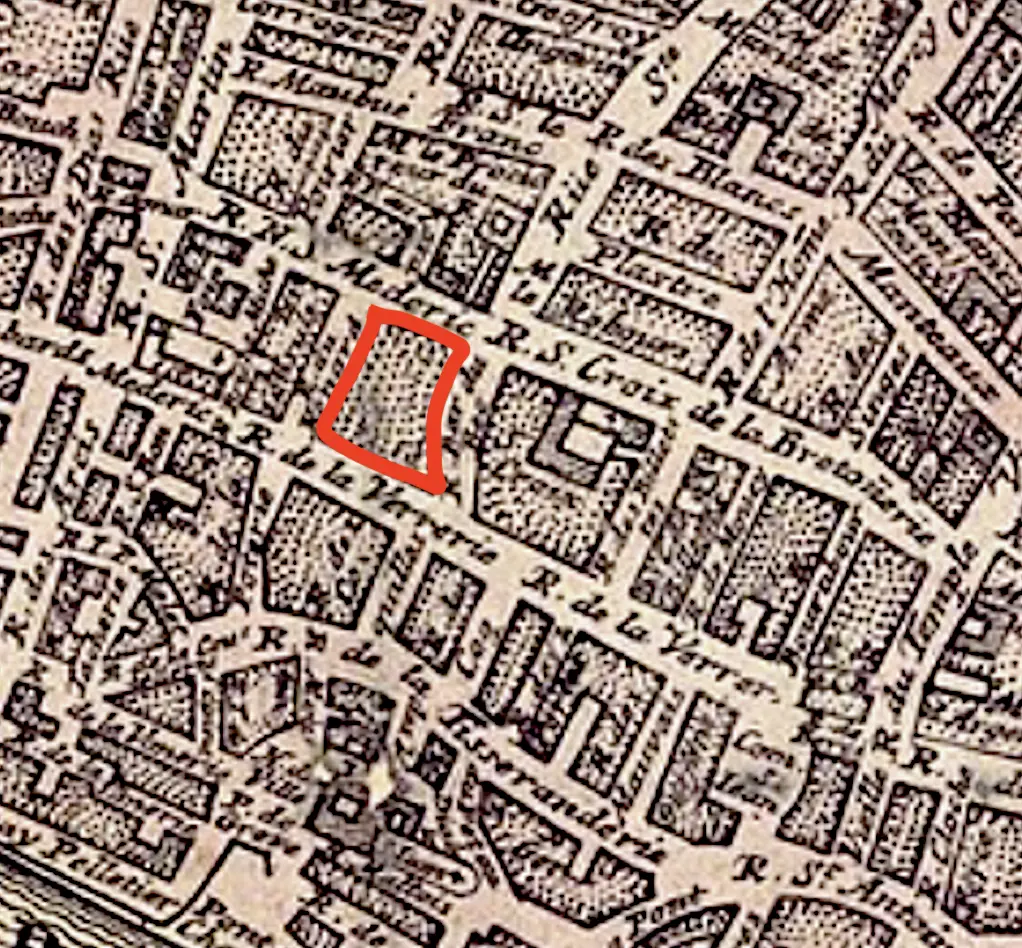

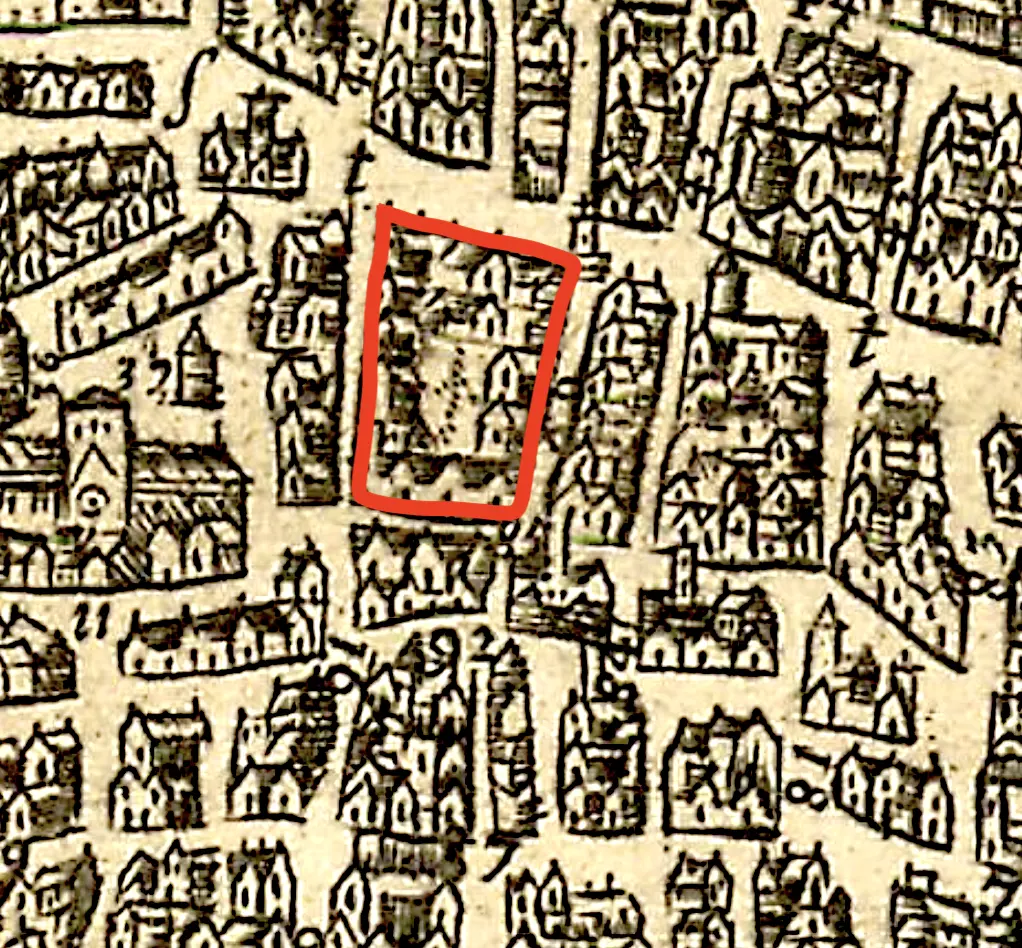

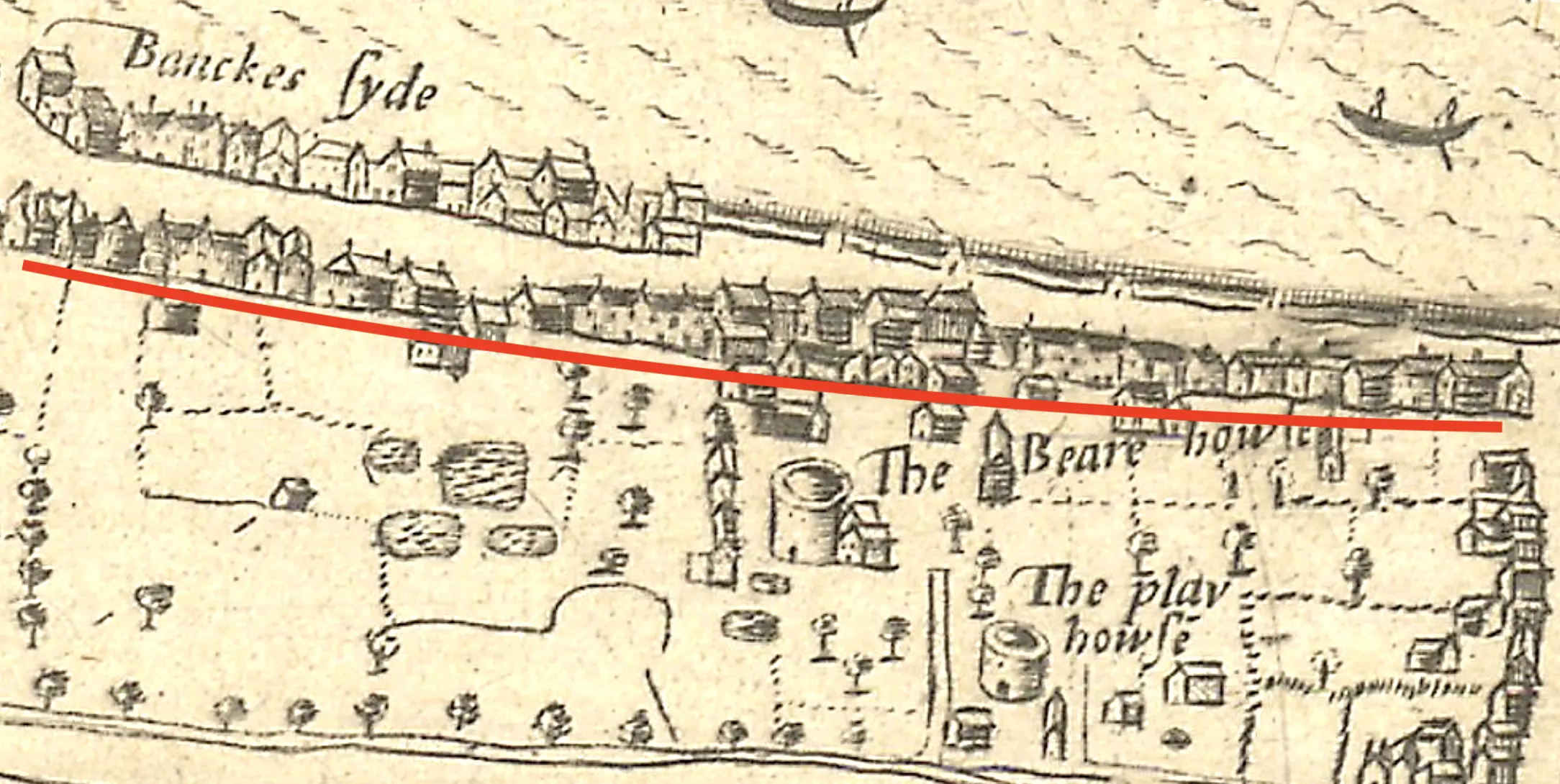

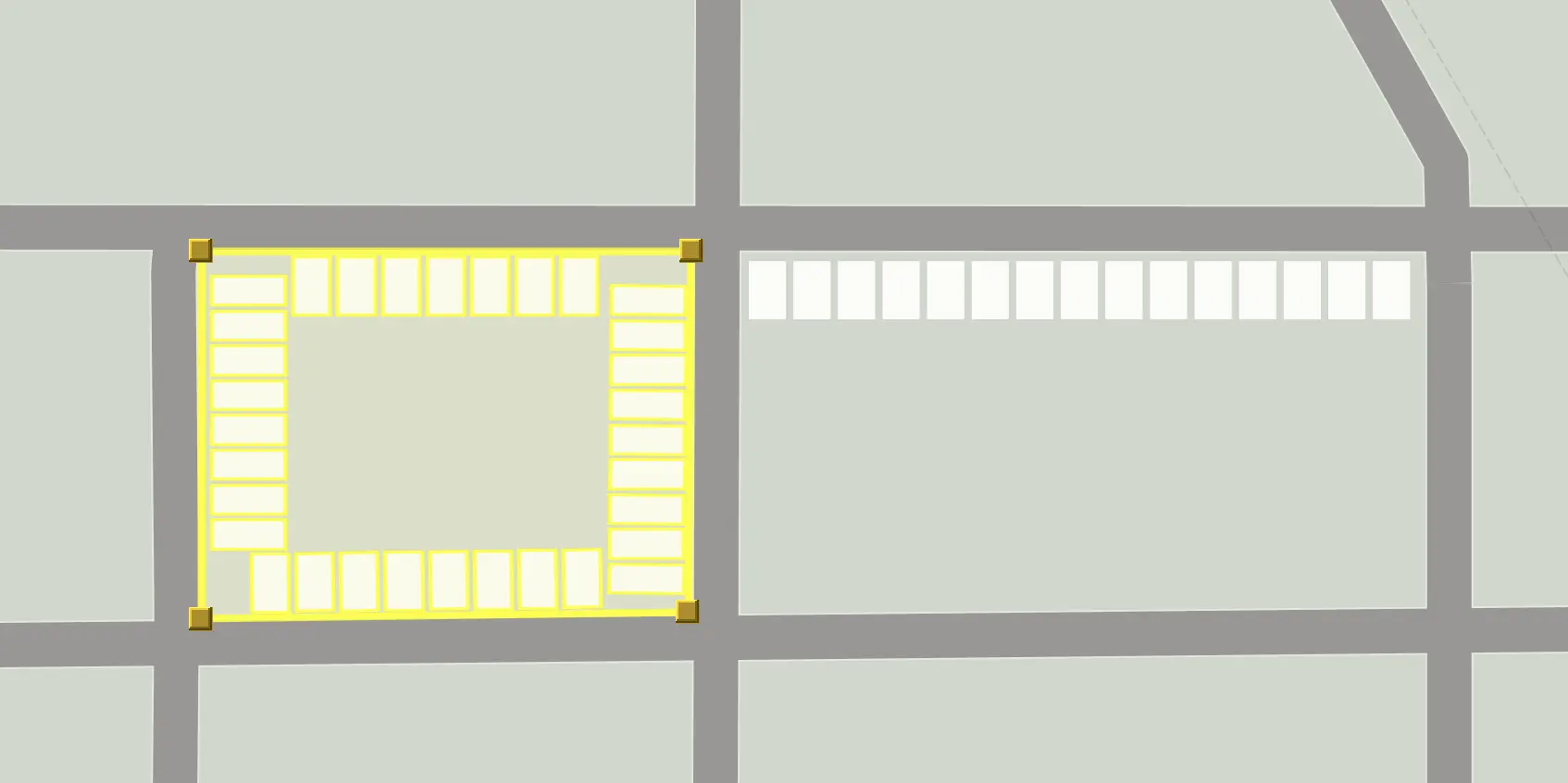

Uncertainty: City Blocks

Historical maps of cities usually did not represent individual smaller buildings separately on the map. They would represent prominent buildings with their footprints, usually in a dark ink, then represent smaller buildings as a more lightly shaded block. These blocks did have discrete buildings, but there is no way to know their exact nature from the map. An individual building in such a block on a 1720 map might be the same building in such a block from a 1680 map, but it might not. Without specific records, there is no way to be sure.

Another common historical representation is of a line of generic buildings. Often seen on artistic representations of cities, such as a painting or illustration from a nearby hill, these indicate there were lines of buildings along streets. However, the buildings are usually just a few simple strokes of the pen and not specific evidence of exact buildings, their architecture, or the exact number.

To model this uncertainty and to keep Running Reality factoid data as close to the source material as

possible, we have the BlockOfBuildings and LineOfBuildings aggregate types. These

are similar to the Forest and LineOfTrees types for trees and the Crowd

and Queue types for people. Represent the block as an area and the line as just a line and the history

engine will draw generic inferred buildings. This separation allows the factoid data set

to closely represent the actual information we know from the cited historical map

Edit BlockOfBuildings location data using the standard Running Reality region editor controls and

LineOfBuildings using the standard path editor controls.

FUTURE Right now, there are no Structure factoids to control some aspects

of the inferred buildings, but there will be. This can tailor building width, height, and separation, which could be known

from the primary source. The architectural style would also be a factoid.

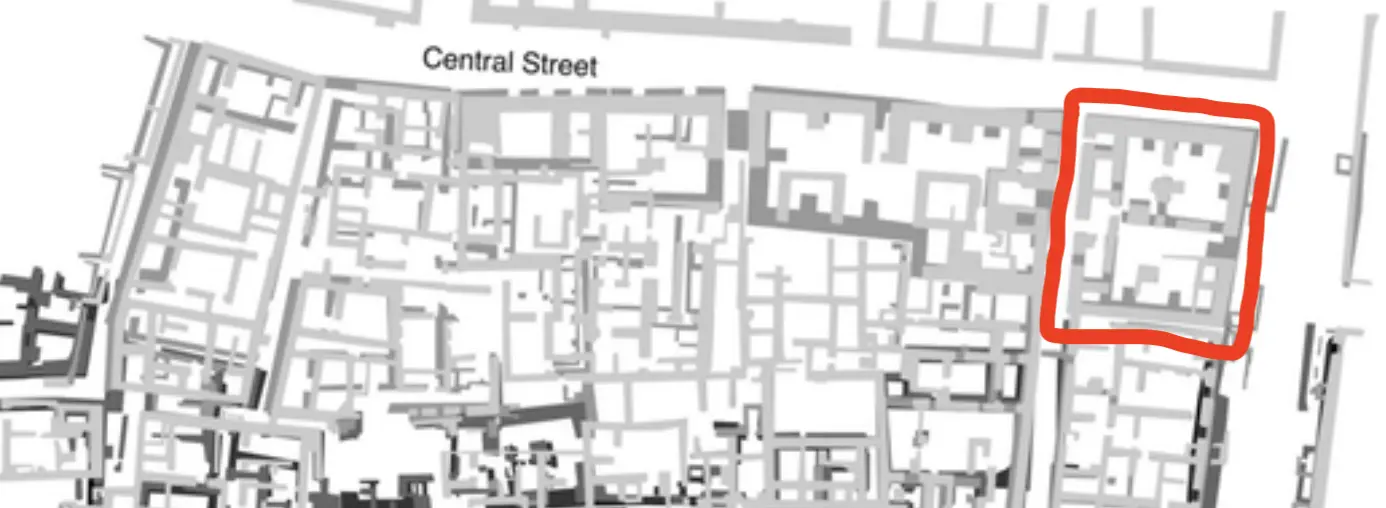

Uncertainty: Shared Walls

In most ancient cities, structures were not usually freestanding. This complicates modeling that is based on a modern concept of property ownership and stand-alone buildings. Today, most buildings have a legal framework for discrete ownership and they stand on property that has the same. There are still cases where a physical wall is shared between buildings, such as in some townhouses, but most buildings are free standing and unconnected to their neighbors.

In most ancient cities, especially those building using stone or brick, outer walls were often shared between buildings. Then, if the city were to be abandoned, and especially if it were to be buried, then the roofs and upper parts of the walls might decay, be sheared off, or be re-purposed by later peoples. The remains today identified on maps of excavations represent the remaining material, which are a combination of outer walls, shared walls, and inner walls. Courtyards, atriums, alleys, and doorways may be identifiable or they may be unclear. For fired mud bricks, used extensively in ancient Mesopotamia, thousands of years of erosion may have "melted" the top bricks into solidified mud that fills the structures.

Here are the criteria to use when determining which partial walls to include in a building or exclude:

- There is a space enclosed with a solid wall with only a small number of doorways to enter and exit the space.

- The space would have had a separate and discrete timeline from an adjacent space. Such as: different family residents, different shops or uses over time, different built dates, etc. Model something separately if it may have a different time evolution.

- There is a space that had been covered with a roof. Roof materials were often organic, such as timbers or thatch. They rarely survived to the present day, but they did exist when the building was in use and often are indicated by wall notches. Roofed area should be represented as part of the building's footprint polygon.

- Do not include an atrium area in the building footprint polygon. If an area did not have a roof, leave it open.

- Do not include interior walls. These will be represented as interior walls when Running Reality can edit more detailed 3D models. When the building is ruined, a model of the ruin would show such walls because then they would be exposed.

Why not just model the walls only exactly as they are today? This is the preferred way to represent the structure in the present day, after it has been ruined. However, that is not an accurate way to represent the building when it was in use. Ruined walls, where the roof and top half of the walls have been sheared off is only one of the building's conditions over its timeline. Note that artistic representations of ancient cities will show the buildings in their functional condition and this kind of representation is traditional and accepted. Ideally, just add data for the building's footprint polygon and let the inference system extrude the walls to full height and choose a generic roof.

3D Structures

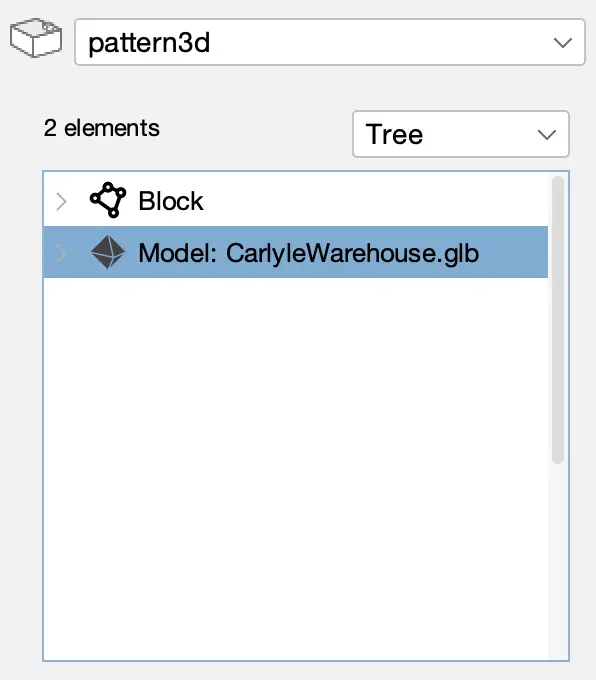

Running Reality is expanding how it represents physical objects by migrating to full 3D. This is being

done step-wise. Any object with physical presence can have a Pattern3D data structure attached

to it. The Pattern3D will have a full Level of Detail (LOD) system for buildings to be cross-compatible between

full 3D models and 2D polygonal footprints.

We are being careful in implementing this system to factor in the following:

- The same history engine inference system must be able to interpolate and extrapolate data over time.

- The source of the data must remain transparent and auditable, even if the structure contains a mixture of provenance.

- Uncertain and composite data, where height, material, architectural style, and condition may be separately cited factoids.

- There is linked data, such as interior spaces being linkable to people or businesses.

- Generative AI is making detailed 3D models more available, but with an extra burden of citation.

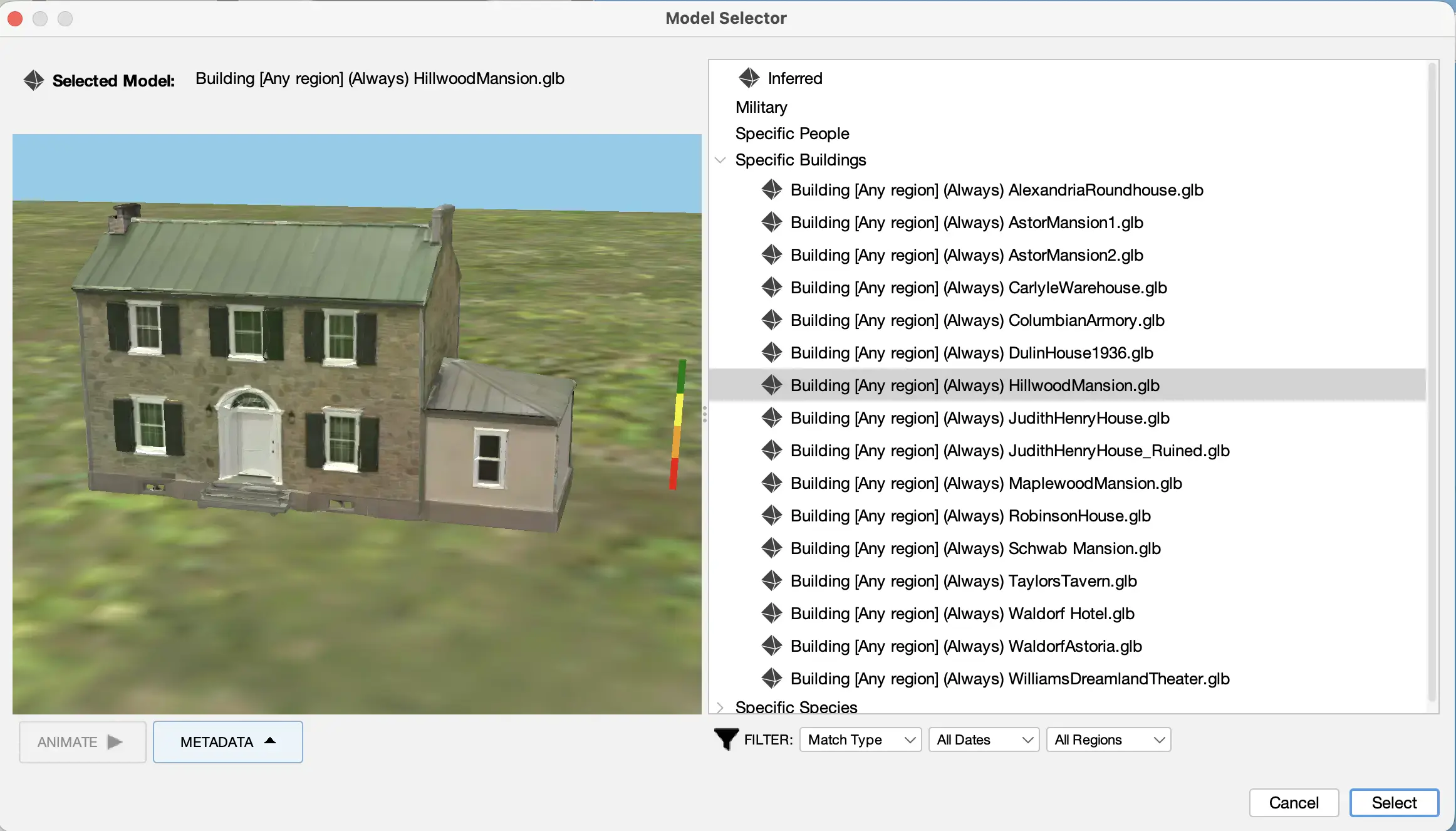

You can see the prototype system for selecting building models if you add a model to the Pattern3D.

This capability is being developed to use Generative AI to take historical photos of buildings and create 3D models.

The models will require specific citation back to the historical photo.

FUTURE There is no user-facing interface yet to convert historical photos into 3D models, but it is being developed.

Summary

This tutorial covers buildings, how they are represented in historical maps and other data, how they are represented in Running Reality, how to edit them, and how to handle uncertainty. As buildings are such a central element of cities, we have worked hard to represent them well and have plans to improve how we represent them into a 3D future.